Building Your Inner Pause Button: How...

The Hidden Power of a Pause How many times have you wished...

-(8).png)

A Collective Indictment from Insiders

These five declarations, spanning forty-five years from 1874 to 1919, were not made by laymen or outsiders. They are the published conclusions of a London public vaccinator, a Cambridge professor, a New York clinician, a medical college professor, and a Swiss professor of hygiene. Together, they form a coherent, devastating, and largely forgotten indictment from within the medical profession itself. They argued that smallpox was often a mild disease exacerbated by contemporary medicine; that its decline was due to sanitation, not the vaccine; and that vaccination was an ineffective and dangerous procedure. The following article examines the evidence behind their claims, re-examining the history of smallpox through the eyes of its most credentialed contemporary skeptics.

Smallpox: A Mistreated Disease?

In the annals of medical history, smallpox is often portrayed as an indiscriminate and deadly menace, a specter of fear that haunted communities for centuries. Conventional narratives depict it as an unrelenting killer, leaving a trail of devastation and claiming the lives of up to 20% of those it infects. It hung like a dark cloud over societies, leaving a legacy of pain and grief.

But what if this portrayal is incomplete? What if smallpox, for many, was not the formidable killer it’s reputed to be, but often a mild disease? On the surface, this seems a heretical idea. However, a consistent thread of historical medical testimony suggests that the disease’s severity was profoundly influenced by contemporary treatments, with some physicians asserting that smallpox was mild when properly managed and catastrophic when mishandled.

In 1688, the esteemed Thomas Sydenham, MD, renowned as the English Hippocrates and regarded as the Father of English medicine, wrote a revealing observation:

“It would be too large for a letter, to give you an account of its history; only in general I find no variolis [smallpox], but do regret greatly, that I did not say, that, considering the practices that obtain, both amongst learned and ignorant physicians, it had been happy for mankind, that either the art of physic had never been exercised, or the notion of malignity never stumbled upon. As it is palpable to all the world, how fatal that disease proves to many of all ages, so it is most clear to me, from all the observations that I can possibly make, that if no mischief be done, either by physician or nurse, it [smallpox] is the most slight and safe of all other diseases.”[6]

Sydenham was reacting against the prevailing “gold-standard” treatment of his era, known as the “hot regimen.” This involved confining the patient in a heated room, swaddling them in blankets to induce sweating, and administering heating cordials, spicy foods, and alcohol. It was believed this would expel the disease. Dr. Sydenham found that these aggressive and erroneous treatments could transform smallpox from a mild illness into a deadly one.

“…the Small-Pox being too much forced out, by giving Cordials, and by a hot Regimen run into one, a foul Spectacle, and one that threatens a sad event; and these and the like Symptoms are usually occasioned by these Errors; whereas I never observed any mischief from the other Method: For Nature, left to herself, does her Work in her own time, and separates, and the expels the Matter in the right way and manner...”[7]

Dr. Sydenham’s alternative approach eschewed these practices, and his peers corroborated its efficacy. In 1681, in a letter to Sydenham, Dr. William Cole expressed gratitude for a method that would “easily cure” smallpox, blaming the standard hot regimen and medicines for countless unnecessary deaths.

“I heartily thank you for your method of Cure in the Small-pox, whereby that dreadful Disease (unless some malignity, of some unusual thing happen, maybe be easily cured) if Nurses, a sort of People very injurious to the Health of Man, did not obstruct, who by the hot Regimen and Medicines, confound all things, and kill so many before their Time. You learned Sir, the Protector of Mankind, ought to be esteemed, who are a guide to the Sick in the greatest Danger of Life, that they may return to the way of Health, if they follow your Direction."[8]

Forty years later, in the early 1700s, Isaac Massey’s observations at Christ’s Hospital indicated that smallpox was rarely fatal when managed with appropriate treatment.[9]

“A natural simple smallpox seldom kills, unless under very ill management, or when some lurking evil that was quiet before is roused in the fluids and confederated with the pocky ferment.”[10]

Drawing from decades of experience at the children’s hospital, which housed around 600 children, he noted an astonishingly low mortality rate, observing that over 20 years, only 5 or 6 deaths were attributed to smallpox. He was so skeptical of the danger of the natural disease that he mocked the new practice of inoculation as “incantation.”

In 1814, John Birch, a distinguished member of the Royal College of Surgeons, expressed a bold and damning conclusion about the primary cause of smallpox fatalities.

“I consider even the Natural Small-pox a mild disease, and only rendered malignant by mistakes in nursing, in diet, and in medicine, and by want of cleanliness… It would hardly be too bold to say, that the fatal treatment of this disease, for two centuries, by warming and confining the air of the Chamber, and by stimulating and heating cordials, was the cause of two-thirds of the mortality which ensued.”[11]

This was not an isolated view. Over the decades, other doctors also observed that smallpox was a mild disease.

“…smallpox is generally a very mild disease…”[12] —Dr. Montague R. Leverson, MD, PhD, 1898

“It [smallpox] is a most harmless disease if properly treated. I have treated hundreds of cases without a single fatality.”[13]—Dr. Smiley, 1907

Collectively, these statements challenge the monolithic image of smallpox as a solitary killer. They prompt a critical historical question: Could these doctors have been right? Was smallpox primarily a mild disease made severe by the general health of the population, poor living conditions, and, most significantly, by the misguided medical doctrines of the time?

The “hot regimen” was a comprehensive and debilitating therapeutic assault. As described in The Cyclopaedia (1819), it created a vicious cycle of deterioration.

“When any person afflicted with any species of fever, is confined in a close and heated apartment, in which the free circulation of air is prevented by closed doors and windows, curtains, &c. and is kept at the same time under a load of bed-clothes, and supplied with hot drinks, or even cordials of vinous and fermented liquors, with the view of inducing perspiration, the consequences are as follow. The whole train of symptoms is aggravated. The heat of the patient is raised considerably above the natural standard, notwithstanding the profuse perspirations that are constantly bathing him; the pulse is excited to the highest febrile standard; the thirst becomes incessant to supply the unnatural waste of fluids; the mouth and lips become parched…the head is in constant pain, with confusion of ideas, preventing all sound sleep, and occasioning distressing dreams, and at length delirium; the whole powers of the frame become prostate, with disposition to fainting, on being moved, or on passing an evacuation by stool; and from this situation the recovery is extremely precarious. In cases of contagious fever, such as small-pox, measles, scarlet-fever, &c, the eruption is always greatly multiplied by this hot regimen, and all the symptoms changed to what has been called a putrid type; the tongue, teeth, and lips, become coated with black, clammy, and immovable fur; purple spots appear on the skin; and the whole disease assumes the character of malignancy.”[14]

This harmful treatment was applied indiscriminately, even to those who had been inoculated. In 1864, Dr. John Mason Good noted its devastating effect.

“Unfortunately, the practice of treating the disease [smallpox] with cordials and a hot regimen at this time prevailed, and was too generally applied to the inoculated as well as to the natural process, by means of which the former was often tendered a severe, and, in many cases, a fatal disease.”[15]

The hot regimen was just one element of a destructive medical arsenal. Standard practices also included aggressive bleeding (phlebotomy), forced purging, and the administration of toxic drugs like calomel (mercury). In 1747, Charles Perry, MD, outlined the protocol.

“Bleeding (which is now very generally practised amongst us, where Small Pox is expected, and even when it has just made its Appearance) is the first Thing necessary to be done; and ought to precede every Thing else... I advise Bleeding copiously... And this I advise to every one indiscriminately, without Regard to Age, Sex, or Temperament… The next Thing I advise, is to give a Vomit... This Medicine is evidently calculated to cleanse and empty the whole alimentary Tube, for it will purge as well as vomit…”[16]

Calomel was a particularly pernicious staple, a potent cathartic and purgative believed to cleanse the body. As noted by Dr. H. G. Cox at New York Medical College in the mid-1800s:

“There is much truth in the statement of Dr. Hughes Bennett, that blood-letting is always injurious, and never necessary, and I am inclined to think it entirely correct. Bleeding in pneumonia doubles the mortality. Calomel does no good in pneumonia. The fewer remedies you employ in any disease, the better for your patient. Mercury is a sheet-anchor in fevers; but it is an anchor that moors your patient to the grave.”[17]

By the mid-19th century, a growing chorus of physicians began to condemn these centuries-old practices. Samuel Dickson, MD, in 1855, offered a scathing indictment:

“For upwards of twenty-three centuries to starve, bleed, purge, and torture, had been the all but exclusive business of the man of medicine. From the days of Hippocrates till within the last few years, this was the undoubted practice in almost all diseases. In truth, what from the gloom of the sick room, and what from the obscurity that enveloped the science, no question was ever asked by the public at large about medical matters. The possession of a diploma or degree from a school or university of reputation was the only requisite for practice. The practice itself, no matter how destructive, signified little so long as it was the ‘established practice.”[18]

The logical conclusion was starkly drawn by Dr. Henry G. Hanchett in 1889: the treatments themselves were often fatal.

“We can recognize the mistakes of our predecessors and those of some of our contemporaries. We wonder that the old-time doctor did not suspect that his lancet, his calomel and tartar emetic, put many a patient underground, whose disease would have ended in recovery if it had been let alone. We are ready to admit frankly that in the past many patients have unquestionably “died of the doctor;” in fact this very disease, variola [smallpox], is a case in point, for the change in the death rate… as compared with earlier records, leaves no possible doubt that mistaken treatment had more than anything else to do with the great mortality of the scourge. Some of us can see very plainly that our colleagues, who are to-day puzzling their brains to explain the terribly increased mortality of pneumonia, need only to leave their hypodermic syringes and morphine at home to find the solution of their problem.”[19]

The Deadly Killer Turns Mild

A profound epidemiological shift occurred at the end of the 1800s. The severe, deadly presentation of smallpox began to decline as public health improved and lethal treatments were abandoned, giving way to the markedly milder presentation that numerous doctors had long described. After 1897, the high-mortality type virtually vanished from the United States. The case fatality rate plummeted from approximately 20% to as low as 1 in 380 (0.26%). This new “variola minor” was so mild it was often mistaken for chickenpox.

“During 1896 a very mild type of smallpox began to prevail in the South and later gradually spread over the country. The mortality was very low and it [smallpox] was usually at first mistaken for chicken pox.”[20]

By the early 1900s, some recognized that sanitation had achieved what vaccination had failed to do—conquer smallpox. Smallpox vaccination was in decline, yet smallpox, like other diseases, was diminishing in significance. In 1914, Dr. C. Killick Millard wrote in his book The Vaccination Question in the Light of Modern Experience: An Appeal for Reconsideration:

“For forty years, corresponding roughly with the advent of the ‘sanitary era,’ smallpox has gradually but steadily been leaving this country (England). For the past ten years the disease has ceased to have any appreciable effect upon our mortality statistics. For most of that period it has been entirely absent except for a few isolated outbreaks here and there. It is reasonable to believe that with the perfecting and more general adoption of modern methods of control and with improved sanitation (using the term in the widest sense) smallpox will be completely banished from this country as has been the case with plague, cholera, and typhus fever. Accompanying this decline in smallpox there has been a notable diminution during the past decade in the amount of infantile vaccination. This falling off in vaccination is steadily increasing and is becoming very widespread.”[21]

C. Killick Millard, The Vaccination Question in the Light of Modern Experience: An Appeal for Reconsideration, 1914, London, pp. 15–17.

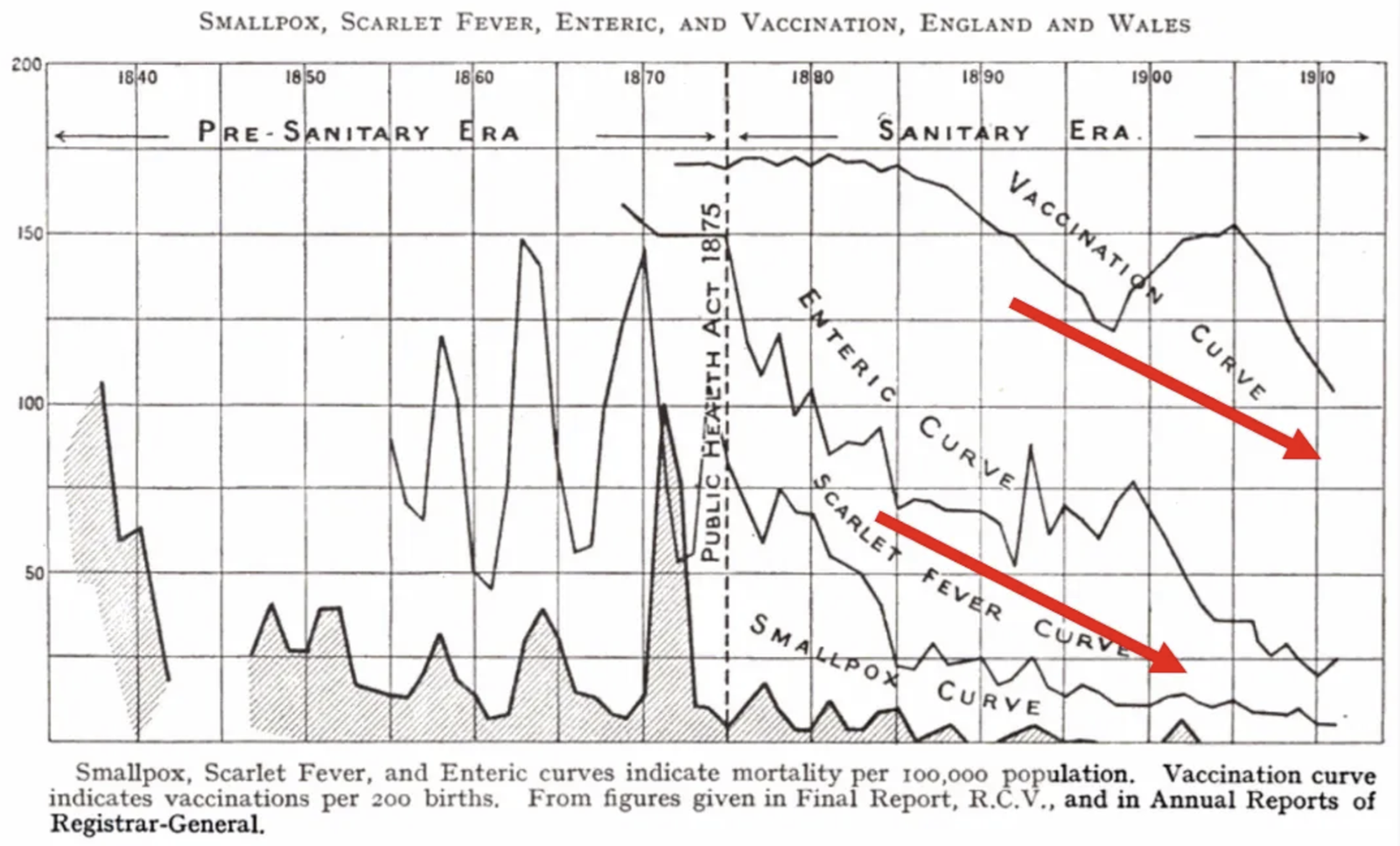

In his 1914 book, Dr. Millard presented a powerful and contrarian argument: the widespread faith the medical profession had placed in vaccination was, in his view, misplaced. He substantiated this claim with compelling statistical evidence, presenting charts of mortality rates for England and Wales. His data revealed a pivotal trend: the decline in deaths from scarlet fever, enteric fever, and smallpox all began concurrently around the 1870s.

Most strikingly, Millard’s analysis highlighted a subsequent and critical development. Beginning around 1885, vaccination rates declined steadily, falling by approximately 40% by 1910. The profound implication was that this dramatic drop in vaccination coincided with no resurgence of smallpox, challenging the established narrative of its necessity and suggesting other factors—likely improved public health and sanitation—were the primary drivers behind the disease’s decline.

“Moreover, it will be noticed that the drop in the mortality from “other zymotics” was almost as striking. So much is this the case, that, without being informed, it is difficult to tell which line represents small-pox, and which “other zymotics.” Obviously, causes other than vaccination must have been at work to have produced this fall in “other zymotics,” and we cannot say that the same cause did not also influence the mortality from smallpox.”[22]

Statistical evidence was compelling. A 1913 analysis showed the case-fatality rate declined from 20.84% in 1895 to 0.26% in 1908—a 98.7% reduction—during a transition that began as the old arm-to-arm vaccination method was phased out.

“Smallpox had become a mild illness, with a significant decrease in its fatality rate. The fatality rate of 20.84% in 1895 had dropped to an astonishing 0.26% [98.7% decrease].”[23]

“On the whole the disease seems to have shown a tendency to diminish, somewhat in severity. This tendency is not marked and the somewhat lower case fatality noted in later years may be due to the better recognition of cases, now that the type has become more widely known. At first fatalities of 1 to 2 per cent and even more were commonly reported, while later fatalities have often been much less. Thus in North Carolina in 1910 there were 3,875 cases with 8 deaths, a fatality of 0.2 per cent, and in 1911 there were 3,294 cases in that state without a single death.”[24]

Something changed to make smallpox a much less lethal and morbid disease, with no secondary fever and little, if any, discomfort. The smallpox eruptions were often fewer than a dozen. The redness usually disappeared in three or four weeks, leaving no permanent marks.[25] In the absence of an epidemic, a case of mild smallpox was likely to be overlooked or mistaken for chicken pox.

“...chickenpox, is a minor communicable disease of childhood, and is chiefly important because it frequently gives rise to difficulty in diagnosis in cases of mild smallpox. Smallpox and chickenpox are sometimes very difficult to differentiate clinically.”[26]

By the 1920s, it was recognized that the new mild form of smallpox produced minimal symptoms, even though few people had been vaccinated.

“Individual cases, or even epidemics, occur in which, although there has been no protection by vaccination, the course of the disease is extremely mild. The lesions are few in number or entirely absent, and the constitutional symptoms mild or insignificant.”[27]

By the 1920s and into the 1930s, mild smallpox had almost wholly replaced the severe form in the United States. There were, however, exceptions, with outbreaks in seaports and near the Mexican border. Once the mild type of smallpox became prevalent, there was no evidence that it ever reverted to the older, more deadly type.

“Although mild cases of smallpox were known before, they have come practically to replace the severe forms in many extensive areas, such as the whole United States, Brazil, large parts of Africa.”[28]

“The mild form of smallpox commonly designated by its Portuguese name, alastrim, has prevailed over vast regions of the United States for over 30 years. It is estimated that the germ of this disease must have been transmitted from one human being to another more than 800 times and yet it is bred true. Throughout all these “generations” the organism maintains its early characteristics... Most American health officers and epidemiologists who have experience with the two types of smallpox do not believe that, as yet, there has been any reversion of the mild strain to the old classic strain.”[29]

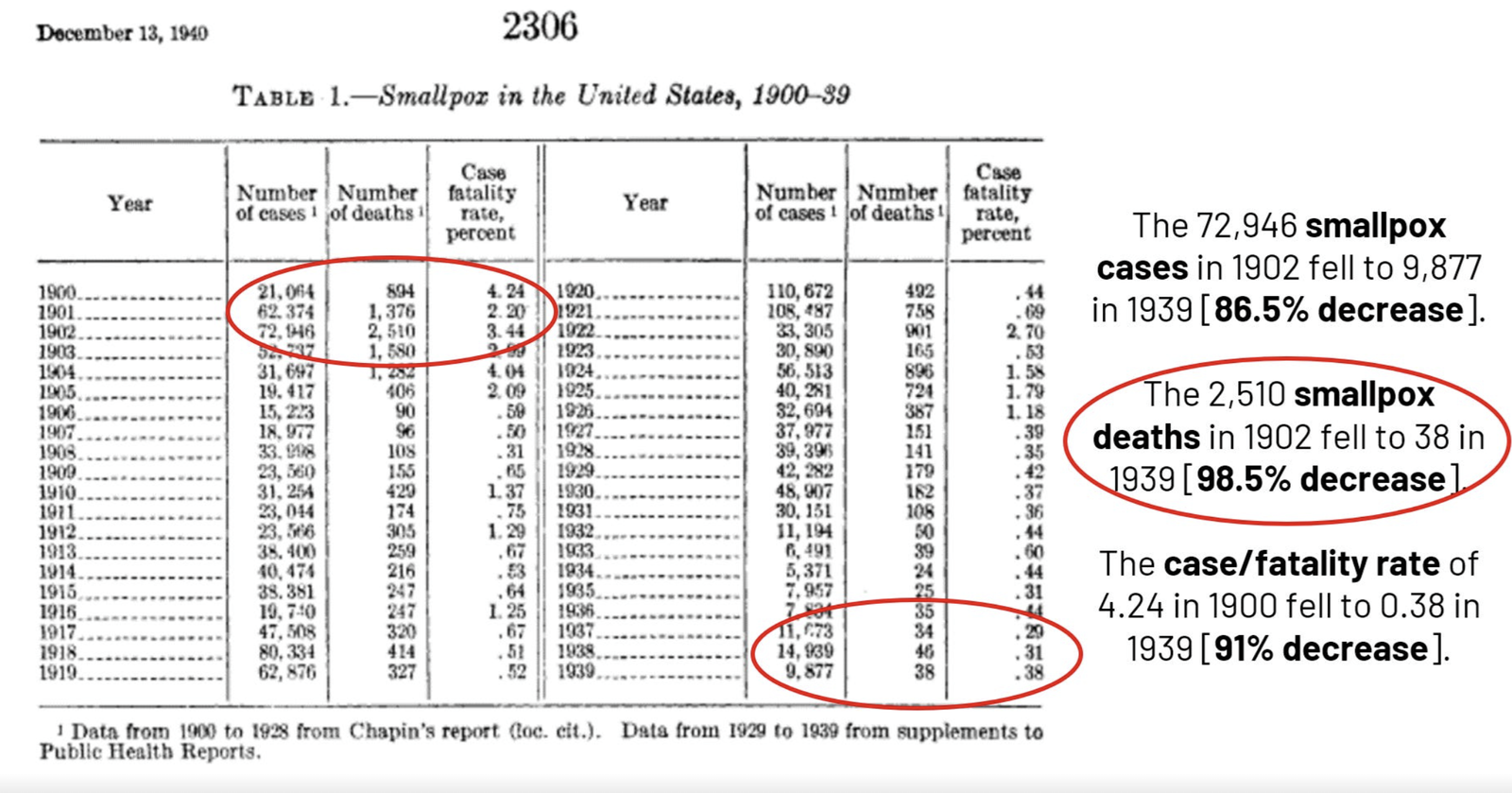

A 1940 article in Public Health Reports showed the ever-downward spiral of smallpox – cases, case/fatality rate, and deaths all plummeted.[30]

“Smallpox in the United States: Its decline and geographic distribution,” Public Health Reports, vol. 55, no. 50, December 13, 1940, pp. 2303-2312.

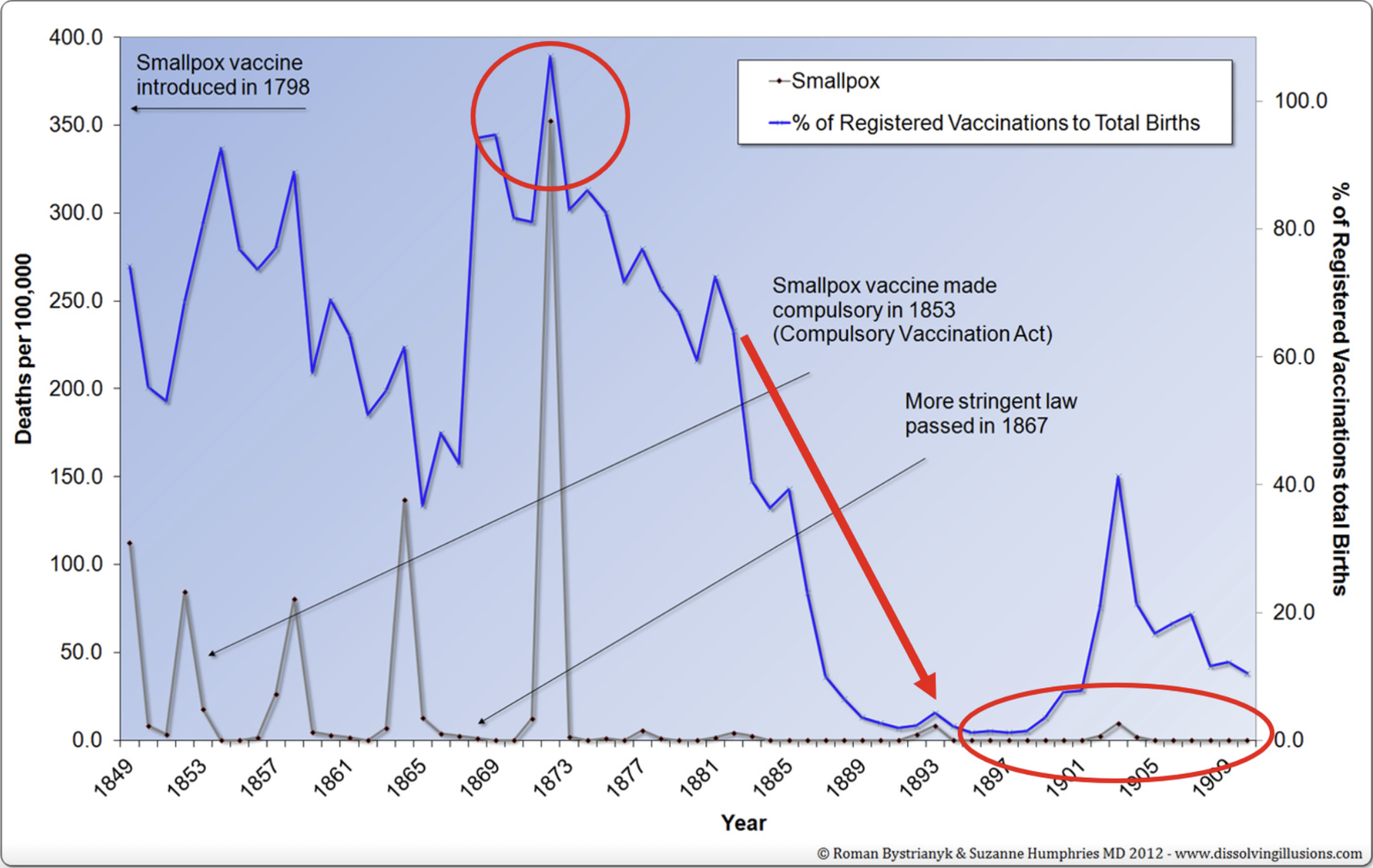

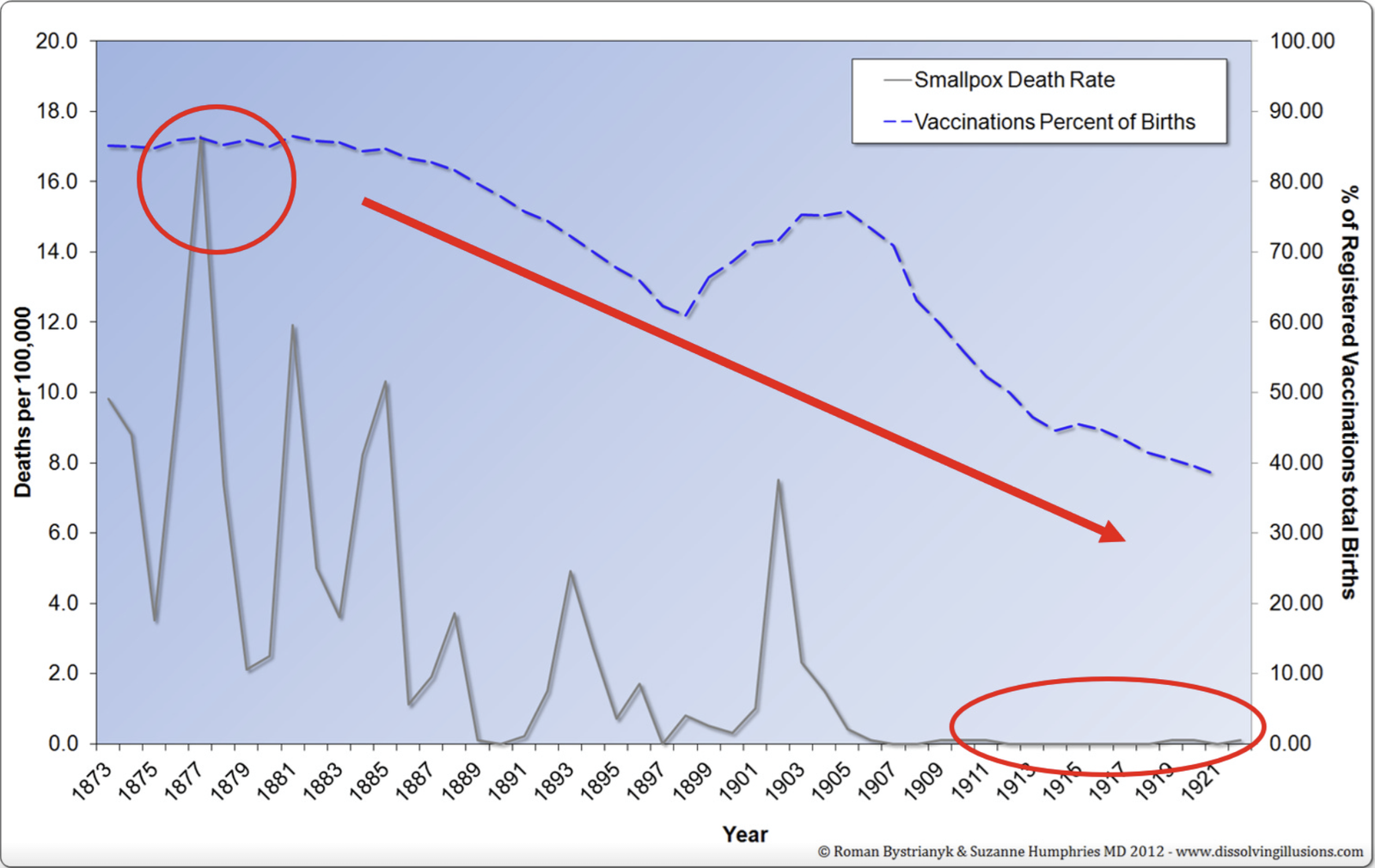

Smallpox incidence declined as smallpox vaccination rates fell, as shown by the data from Leicester, England, and England & Wales.

Leicester, England smallpox mortality vs. vaccine coverage from 1849 to 1910.

England and Wales smallpox mortality vs. vaccine coverage from 1873 to 1922.

By the time the following report was written in 1946, smallpox had all but vanished from England and the Western world. The health of people had dramatically improved. The hot regimen, bleeding, and calomel were largely no longer in medical fashion and were quickly forgotten.

“What has been the cause of the rise and fall of smallpox? Its decline in the later decades of the nineteenth century was at one time almost universally attributed to vaccination, but it is doubtful how true this is. Vaccination was never carried out with any degree of completeness, even among infants, and was maintained at a high level for a few decades only. There was therefore always a large proportion of the population unaffected by the vaccination laws. Revaccination affected only a fraction. At the present the population is largely entirely unvaccinated. Members of the public health service now flatter themselves that the cessation of such outbreaks as do occur is due to their efforts. But is this so?”[31]

The Vanishing Smallpox Deaths and the Cost of Vaccination

The landmark case was in Leicester, England. After abandoning compulsory infant vaccination in the 1870s in favor of sanitation and isolation, the city saw superior outcomes. In 1948, Dr. Millard noted:

“...in Leicester during the 62 years since infant vaccination was abandoned there have been only 53 deaths from smallpox, and in the past 40 years only two deaths. Moreover, the experience in Leicester is confirmed, and strongly confirmed, by that of the whole country. Vaccination has been steadily declining ever since the “conscience clause” was introduced, until now nearly two-thirds of the children born are not vaccinated. Yet smallpox mortality has also declined until now quite negligible. In the fourteen years 1933-1946 there were only 28 deaths in a population of some 40 million, and among those 28 there was not a single death of an infant under 1 year of age.”[32]

Modern epidemiological analysis supports the thesis that socio-economic development, not universal vaccination, ended endemic smallpox. Dr. Thomas Mack, a leading smallpox expert, observed in the 2000s.

“Disappearance [of smallpox] was facilitated, not impeded, by economic development. Long before the World Health Organization’s Smallpox Eradication Program began, and despite low herd immunity, unsophisticated public health facilities, and repeated introductions, smallpox disappeared from many countries as they developed economically, among them Thailand, Egypt, Mexico, Bolivia, Sri Lanka, Turkey, and Iraq.”[33]

“If people are worried about endemic smallpox, it disappeared from this country not because of our mass herd immunity. It disappeared because of our economic development. And that’s why it disappeared from Europe and many other countries, and it will not be sustained here, even if there were several importations, I’m sure. It’s not from universal vaccination.”[34]

The notion that smallpox was just about a microbe that single-handedly killed millions needs to be questioned. This simplistic idea ignores the feeble health of the people and society during those times, as well as the dangerous and deadly medical practices. As noted by Dr. Eliphalet Kimball in 1867:

“Physicians have slain more than war. As instruments of death in their hands, calomel, bleeding, and other medicines, have done more than powder and ball. The public would be infinitely better off without professed physicians. In weak constitutions nature can be assisted. Good nursing is necessary, and sometimes roots and herbs do good. In strong constitutions medicine is seldom needed in sickness. To a man with a good constitution, and guided by reason, in his course of living, sickness would be impossible.”[35]

Copious bleeding, the hot regimen, and toxic medicines that purged the entire digestive system caused significant harm, turning this disease and many others into a fatal catastrophe. Yet a microbe was 100% blamed for the deaths. It’s analogous to spraying gasoline on a tiny candle inside a home, which could make the whole house burn down, and then entirely blaming the candle for the fire.

By the close of the 1800s, public health had vastly improved, and many erroneous medical notions had all but vanished. Vaccination rates declined rapidly over the decades, becoming more of a problem than a solution. Once again, smallpox had become a mild disease and gradually declined worldwide. However, the idea that smallpox needed to be eradicated through vaccination became a legend, and the only solution was deeply embedded in our medical and societal consciousness.

By the 20th century, as public health improved and deadly treatments were abandoned, smallpox faded. Yet, the narrative of vaccination’s sole triumph became an unassailable legend, deeply embedded in medical and societal consciousness. This belief led to a tragic paradox: the routine vaccine itself became a significant cause of death in the absence of the disease. In 1968, Professor C. Henry Kempe revealed the stark cost.

“The mortality and morbidity from routine infant smallpox vaccination in this country is now truly appalling when compared to the risk of smallpox… Analysis of data obtained from a review of questionnaires received from 19,616 physicians surveyed by us suggested that the estimated number of complications in 1963 was approximately 3,000, with ten to eighteen deaths among a total of fourteen million persons vaccinated… The last smallpox death in the United States following an importation occurred in 1948, but since that time there have probably been 200 to 300 deaths from smallpox vaccination… The majority of workers in the field of public health sincerely feel that the current morbidity and mortality from routine vaccination is ‘the price we have to pay’ for keeping our country free of smallpox.”[36]

The Broader Context: The Universal Decline of Infectious Disease

The dramatic decline in smallpox fatality and incidence did not occur in isolation. It was part of a sweeping, unprecedented historical phenomenon: the collapse of mortality from nearly all major infectious diseases in the industrialized world. This decline began in the late 19th century, driven by what is broadly termed the “sanitary revolution” and rising standards of living.

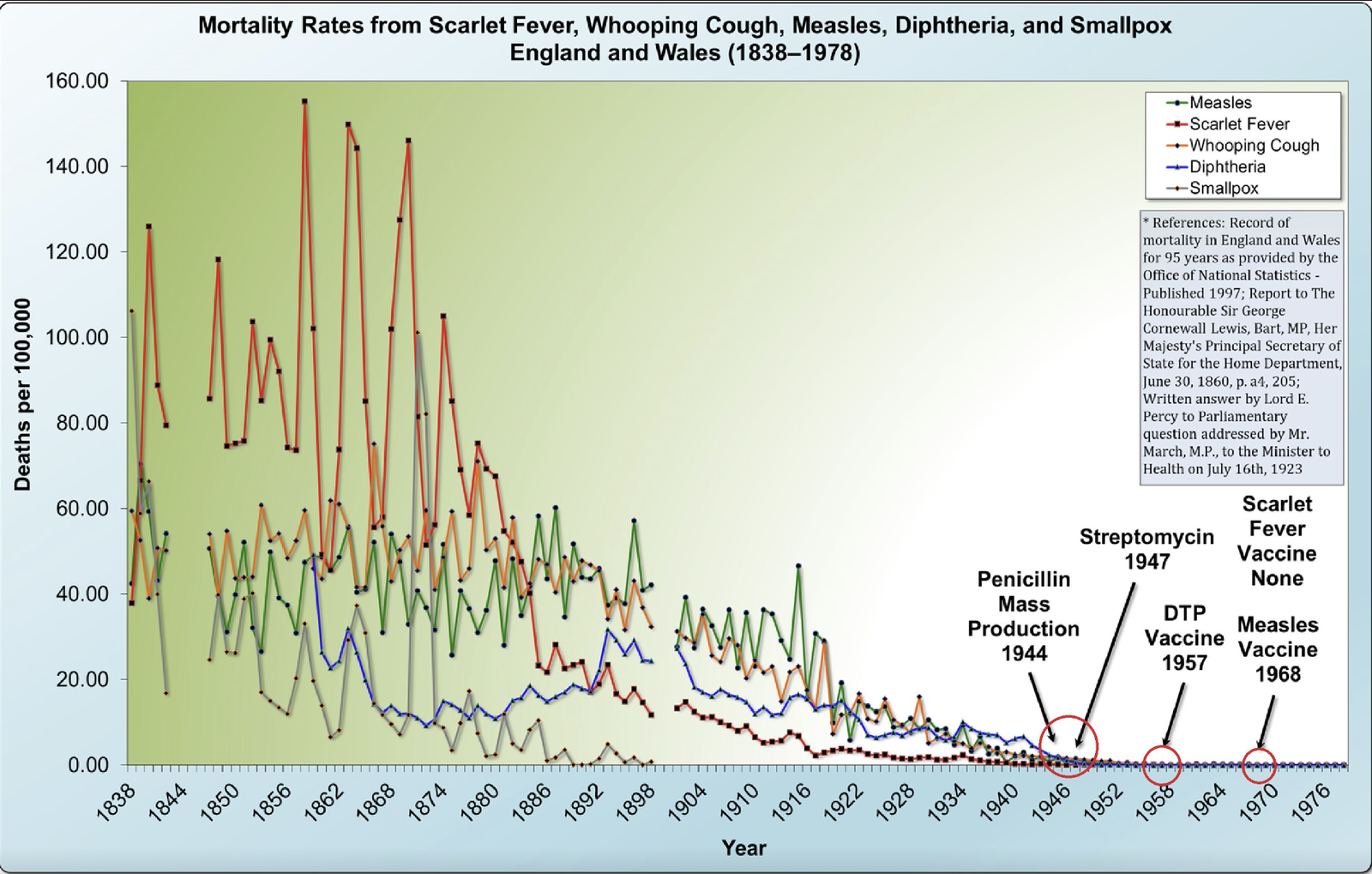

Mortality Rates from Scarlet Fever, Whooping Cough, Measles, Diphtheria, and Smallpox England and Wales (1859–1978)

This universal trend is critical for understanding smallpox. As Dr. Millard’s 1914 chart showed, the mortality lines for smallpox and “other zymotic (infectious) diseases” fell in near-perfect parallel from the 1870s onward. This synchronized collapse points overwhelmingly to a common cause—improvements in sanitation, nutrition (especially reduced malnutrition), clean water, less crowded housing, and the abandonment of harmful medical treatments such as bleeding and heavy-metal purges.

The implication is inescapable: Smallpox did not become mild and retreat because of a unique medical intervention (vaccination) that set it apart from other scourges. It followed the same historical rule as its peers. Its virulence was subdued by the same forces that tamed measles, scarlet fever, and typhoid: a radically improved human “terrain.” The subsequent near-disappearance of endemic smallpox in the developed world by the mid-20th century—coinciding with declining vaccination rates, as seen in Leicester and national statistics—suggests that vaccination may have been, at best, a secondary factor riding the powerful wave of this broader socio-economic transformation.

Conclusion

By the close of the 1800s, public health had vastly improved, and many erroneous medical notions had all but vanished. Vaccination rates declined rapidly over the following decades. Smallpox, having become a mild disease for most, gradually declined in the Western world, mirroring the fate of other once-deadly infections. This was not a unique medical triumph but a demographic one, shared by measles, whooping cough, scarlet fever, and typhoid, all of which saw 90-100% declines in mortality before the advent of specific vaccines or antibiotics.

However, the compelling narrative that a targeted medical intervention—vaccination—had specifically conquered this singular plague became an unassailable legend, deeply embedded in our medical and societal consciousness. This belief led to a tragic paradox in the 20th century: the routine vaccine itself became a significant cause of death and injury in the absence of the disease.

This entrenched paradigm of defeating microscopic “enemies” was then extended to other diseases, often overlooking the crucial historical context: every infectious disease mortality rate had already declined substantially due to improved living conditions before any vaccine was introduced. The subsequent introduction of vaccines, while potentially suppressing incidence, was credited with victories won mainly due to decades of prior societal progress.

Yet with sufficient indoctrination and repetition, mythology becomes a collective illusion; that doesn’t make it true. As Giordano Bruno said over 400 years ago, “It is proof of a base and low mind for one to wish to think with the masses or majority, merely because the majority is the majority. Truth does not change because it is, or is not, believed by a majority of the people.”

“Unfortunately, a belief in the efficacy of vaccination has been so enforced in the education of the medical practitioner that it is hardly probable that the futility of the practice will be generally acknowledged in our generation, though nothing would more redound [contribute] to the credit of the profession and give evidence of the advance in pathology and sanitary science. It is more probable that when, by means of notification and isolation, small-pox is kept under control, vaccination will disappear from practice, and will retain only a historical interest.”[37]

— Professor E. M. Crookshank, MRCS, Professor of Comparative Pathology and Director of the Bacteriological Laboratory, King’s College, London, 1889

...

“The nearly general declaration of my patients enables me to proclaim that vaccination is not only an illusion, but a curse to humanity. More than ridiculous—it is irrational—to say that any corrupt matter taken from boils and blisters of an organic creature could affect the human body otherwise than to injure it… I myself know the names of a hundred physicians who think like me.”[1]

— Dr. Stowell, a London public vaccinator for thirty years, 1874

“In a small town of Brunswick, forty-nine children were vaccinated with lymph ‘of the clearest and freshest kind,’ and with a typically correct result, during the months of June and July, 1801. In the course of August, September, and October, following, forty-five of these same children caught smallpox in the epidemic.”[2]

— Dr. Charles Creighton, MD, professor at the University of Cambridge, 1890

“There they have had a royal commission on inquiry, and the evidence was overwhelming to prove: (1) That vaccination affords not the least protection against smallpox. (2) that smallpox is generally a very mild disease; and (3) that cowpox is often a very dangerous one.”[3]

— Dr. Montague R. Leverson, MD, MA, PhD, Staten Island, NY, 1898

“I am firmly convinced (1), that vaccination never protected against smallpox, and never has been relied upon to do so; (2) that smallpox, like other zymotic diseases, has decreased because of our better sanitary and hygiene conditions and the disinfection and isolation practiced when the disease is present; (3) that vaccination, as practiced now and at all times since its introduction, has caused untold suffering to countless thousands of helpless victims, and that disease, life-long suffering and death have followed in its trail.”[4]

— Professor Robert Alexander Gunn, MD, New York Medical College, New York, 1903

“After collecting the particulars of 400,000 cases of smallpox, I am compelled to admit that my belief in vaccination is absolutely destroyed.”[5]

— Dr. Adolf Vogt, Professor of Medicine and Hygiene, Berne University, Switzerland, 1919

References:

1. A New Year’s Gift to the Lord Provost, Magistrates, and Town Council of the City of Glasgow, 1st January, 1874. p. 46.

2. Dr. Charles Creighton, MD, “Vaccination: A Scientific Inquiry,” The Arena, September 1890, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 436–437.

3. The Public, August 27, 1898, no. 21, p. 5.

4. Order to Show Cause. N. Y. SUPREME COURT, KINGS COUNTY, In the Matter of The Application of Edmund C. Viemeister for a Peremptory Writ of Mandamus, Patrick J. White, President of the Board of Education, and F. H. Meade, Principal of Public School No. 12. Borough of Queens Supreme Court: Appellate Division-Second Department, 1903, pp. 5–10.

5. “Vaccination,” The Theocrat, vol. VI, no. 41, November 22, 1919.

6. R. G. Latham, MD, The Works of Thomas Sydenham, MD, vol. I, 1848, London, pp. lxxii–lxxiii.

7. John Pechey, MD, The Whole Works of that Excellent Practical Physician Dr. Thomas Sydenham, MD, 1696, London, p. 100.

8. John Pechey, MD, The Whole Works of that Excellent Practical Physician Dr. Thomas Sydenham, MD, 1696, London, p. 404.

9. Isaac Massey, apothecary to Christ’s Hospital, A Short and Plain Account of Inoculation, 1722, London, pp. 20–21.

10. Isaac Massey, Remarks on Dr. Jurin’s Last Yearly Account of the Success of Inoculation, 1727, London, p. 5.

11. The Gentleman’s Magazine, July 1814, p. 24.

12. The Public, Chicago, Saturday, August 27, 1898, no. 21, p. 5.

13. The Parliamentary Debates, 1907, vol. CLXIX, p. 408.

14. Abraham Rees, The Cyclopaedia; Or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature, vol. 29, 1819.

15. John Mason Good, MD, The Study of medicine: Empyesis Variola Smallpox, vol 1, 1864, New York, Harper & Brothers, Publishers, pp. 639–640.

16. Charles Perry, MD, An Essay on the Smallpox, 1747, London. pp. 17–20.

17. “Russell Thacher Trall, MD, Water-cure for the Million, 1860, New York, p. 7.

18. Samuel Dickson, MD, Glasgow, The “Destructive Art of Healing;” or, Facts for Families, Second Edition, 1855, London, Geo. Routledge & Co., pp. 5–6.

19. Henry G. Hanchett, M.D., “An Inquiry in Prophylaxis,” The New York Medical Times, vol. XVI, no. 10, January 1889, p. 306.

20. Charles V. Chapin, “Variation in Type of Infectious Disease as Shown by the History of Smallpox in the United States,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 13, no. 2, September 1913, p. 173.

21. Harry Bernhardt Anderson, State Medicine a Menace to Democracy, 1920, p. 84.

22. C. Killick Millard, The Vaccination Question in the Light of Modern Experience: An Appeal for Reconsideration, 1914, London, pp. 15–17.

23. Charles V. Chapin, “Variation in Type of Infectious Disease as Shown by the History of Smallpox in the United States,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 13, no. 2, September 1913, p. 172.

24. Charles V. Chapin, “Variation in Type of Infectious Disease as Shown by the History of Smallpox in the United States,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases, vol. 13, no. 2, September 1913, p. 178.

25. Ibid., p. 179.

26. John Gerald Fitzgerald, Peter Gillespie, and Harry Mill Lancaster, An Introduction to the Practice of Preventive Medicine, 1922, C.V. Mosby Company, p. 197.

27. John Price Crozer Griffith, The Diseases of Infants and Children, Volume 1, 1921, W.B. Saunders Company, p. 370.

28. George Dock, MD, “Smallpox and Vaccination,” Journal of the Missouri State Medical Association, vol. 19, April 1922, p. 168.

29. Charles V. Chapin and Joseph Smith, “Permanency of the Mild Type of Smallpox,” Journal of Preventive Medicine, 1932.

30. “Smallpox in the United States: Its decline and geographic distribution,” Public Health Reports, vol. 55, no. 50, December 13, 1940, pp. 2303-2312.

31. Journal of the Royal Sanitary Institute, vol. 66, 1946, p. 176.

32. C. Killick Millard, MD, DSc, “The End of Compulsory Vaccination,” British Medical Journal, December 18, 1948, p. 1074.

33. Thomas Mack, MD, “A Different View of Smallpox and Vaccination,” New England Journal of Medicine, January 30, 2003, pp. 460–463.

34. Transcript of the Meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices held at the Atlanta Marriott Century Center, Atlanta, Georgia, on June 19 and 20, 2002.

35. Dr. Eliphalet Kimball, Thoughts on Natural Principles, 1867.

36. C. Henry Kempe, “Smallpox vaccination of eczema patients with attenuated live vaccinia virus,” Yale journal of biology and medicine, August 1968, pp. 9–10.

37. Edgar March Crookshank, History and Pathology of Vaccination Volume 1: A Critical Inquiry, 1889, London, pp. 465–466.

Image source: Andrii Zorii

Note: The views expressed here do not exclusively represent the views of Materia+ and governing entities.

Check out these recently published articles on Materia+.

The Hidden Power of a Pause How many times have you wished...

The incidence of gluten intolerance, celiac disease and other health problems linked...

A Collective Indictment from Insiders These five declarations, spanning forty-five years from...

Vaccinosis is the term given to those conditions that are a direct...